A Future So Bright

Score 1 for Health has worked with underserved populations in the Kansas City region for decades.

By Elizabeth Alex

Although they suspected serious impairment, Mason’s new teachers first learned the extent of his vision problems at the annual OneSight clinic held on the campus of Kansas City University (KCU). “Once they tested him, they realized he couldn’t see his hand in front of his face,” said Sue Hoffman, a teacher at Our Lady of Hope grade school.

Mason received two pairs of glasses, made on the spot. “It was amazing,” Hoffman remembers. “When they put a mirror in front of his face, his eyes got big and he just kept looking at his face. He was amazed at the water bubbling in the fountain. He touched the bricks he could see on the building and knelt down and saw blades of grass for the first time.”

Across the United States, tens of thousands of school children aren’t as fortunate as young Mason. Their vision problems go unaddressed, impacting their ability to learn, their childhoods and ultimately their futures.

According to an Education Week Research Center analysis of a National Survey of Children’s Health Data, one-third of school children have not had a vision screening in at least two years, if at all.

Annette Campbell, executive director of KCU’s outreach program Score 1 for Health, has worked with underserved populations in the Kansas City region for decades and knows the problem well. Through Score 1, KCU medical students screen more than 14,000 Kansas City and Joplin-area school children per year in several areas of health, including vision. Campbell explains there are a multitude of reasons these children are not getting the exams they need.

“Parents often don’t have transportation, time off work or money to pay for a vision exam and glasses. Language barriers also are a challenge,” she said.

A partnership of smiles and impact

OneSight is the global charitable arm of Luxottica, a company that sells glasses around the world. KCU partners with OneSight and Fidelity Security Life (FSL)Insurance Company, which underwrites part of the cost and coordinates a team of volunteers, including FSL employees, KCU medical students and local optometrists. Once a year the team arrives on campus with eye charts, refracting machines, frames and the equipment needed to make glasses. The annual OneSight week is full of smiles at the direct impact of the university mission to "improve the well-being of the communities we serve."

“The energy of the OneSight program here on our campus is palpable,” said Marc B. Hahn, DO, president and CEO of KCU. “We all enjoy seeing the kids’ excitement at getting glasses and being able to see. Sight is important for all of us, but especially for kids. If you can’t see, you can’t read. And if you can’t read, you can’t learn.”

“The energy of the OneSight program here on our campus is palpable,” said Marc B. Hahn, DO, president and CEO of KCU. “We all enjoy seeing the kids’ excitement at getting glasses and being able to see. Sight is important for all of us, but especially for kids. If you can’t see, you can’t read. And if you can’t read, you can’t learn.”

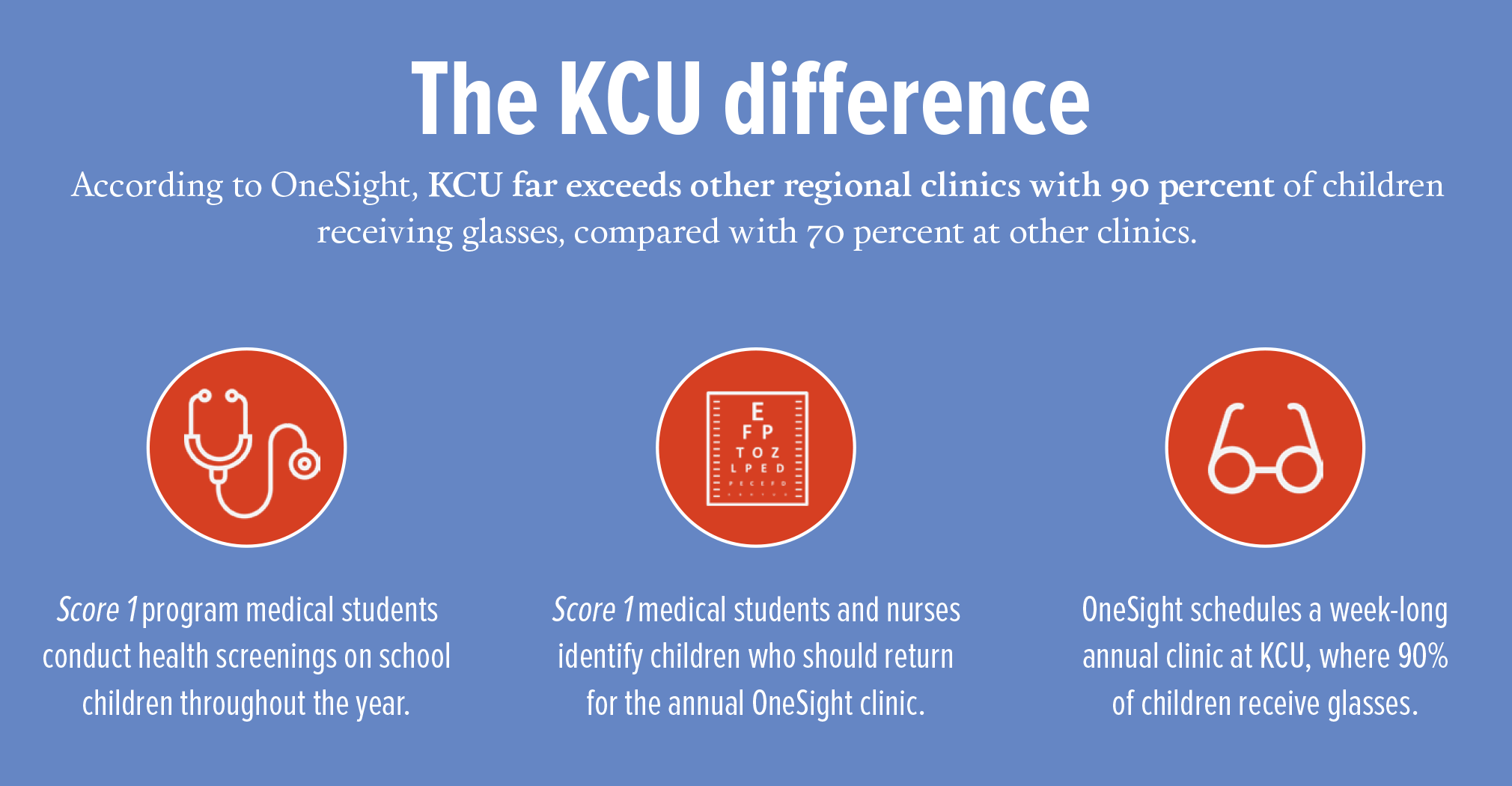

In order for the week-long clinic to be successful, children with vision problems must be identified before the OneSight team arrives. That is where Score 1 for Health is crucial. Most of the kids who come to the clinic are screened by Score 1 medical students and nursing students from partner colleges and universities in preplanned screening days in elementary schools. The children walk in the door ready for an examination.

“When opportunities like this arise, we have the data and information to get kids into a clinic like this,” said Campbell. “They come in quickly and efficiently. We provide a comprehensive report and fine tune it to the children who have the most severe vision loss. That gets the kids in who need glasses the most.”

Melinda Everley, of FSL started the OneSight program in Kansas City 10 years ago. She says during that first year, they were able to provide glasses to roughly 60-70 children. This year that number rose to 662.

“There are a lot of children in the world who can’t see. We want to catch them as early as we can,” Everley emphasized. “That first year we had glasses to give, but we didn’t have children who were pre-screened. This partnership has made a huge difference.” Due to the partnership with Score 1 and KCU, OneSight considers the week they spend in Kansas City a great success.

“There are a lot of children in the world who can’t see. We want to catch them as early as we can,” Everley emphasized. “That first year we had glasses to give, but we didn’t have children who were pre-screened. This partnership has made a huge difference.” Due to the partnership with Score 1 and KCU, OneSight considers the week they spend in Kansas City a great success.

“The clinic at KCU far exceeds our other regional clinics in terms of the percentage of children who receive glasses,” said Steve Stockton, clinic manager.

“Other clinics average about 70 percent of kids needing glasses. Since Score 1 has been involved, KCU’s average has been over 90 percent. It is because of the excellent pre-screening that the Score 1 program does,” said Stockton.

The OneSight clinic also offers KCU medical students experience in ophthalmology and working with pediatric patients.

Full Circle

For first-year medical student Neha Singh, it’s personal. She worked for Luxottica in sales at Sunglass Hut stores as she earned her undergraduate degree, and she continues to work there through medical school. Singh often asks customers to give to OneSight and she donates as well. Singh eagerly agreed to volunteer at the OneSight clinic despite the fact she had two challenging tests the next day and could have used her time to study.

“This brings my experience with the company full circle,” she said. “I got to see kids who were almost blind and couldn’t read the largest letters on the screen and afterwards be able to read them. There were kids who said they had glasses five years ago, but their prescriptions had changed and they couldn’t afford to get new ones. And there were kids who had broken glasses tied with tape. I recommend med students take time out of busy schedules to help others. That is what will make us truly empathetic physicians.”

For kids like Mason, the OneSight clinic offers a critical continuum of care. He returned for a new prescription this year, clutching a stuffed animal named Cat-Cat, who sported his own new pair of glasses at the end of the day.

“Oh my gosh this is a Godsend for our kids,” Hoffman said. “Thank you for all your help. You and all of the people who put this clinic together are the ones who give us hope.”