“We’re training skeptics and detectives,” said Jeffrey Staudinger, PhD, professor of pharmacology at Kansas City University (KCU). “These students will leave not just knowing more about cancer biology, but also how to ask the right questions — a skill every good clinician needs.”

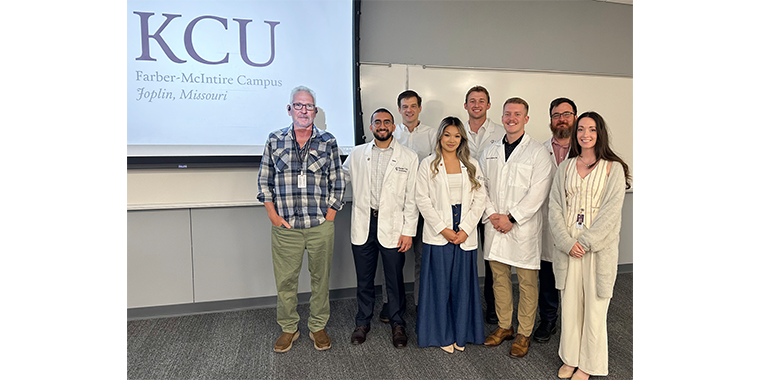

Guided by Staudinger and Bradley Creamer, PhD, KCU chair and professor of Basic Sciences, five students — three studying medicine and two studying dentistry — spent their break from coursework in the Summer Student Research Fellowship, (SSRF) an eight-week program offering students the chance to conduct research under faculty mentorship. Their projects were conducted as part of a larger initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Cancer Institute.

Worth nearly half a million dollars, the NIH-sponsored grant supports research to understand the role of the pregnane X receptor (PXR) — a protein that helps regulate how the body processes drugs and other substances. The study explores whether PXR may contribute to chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer, a significant challenge in patient management when tumors stop responding to treatment. NIH funding is among the most competitive in the nation, with only a small percentage of applications awarded. Backed by the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world, the grant places the work of KCU alongside projects recognized for their national significance, scientific rigor and potential to advance human health.

For the students, it was both a rare hands-on research opportunity and a prestigious credential that can set them apart in competitive residency placements. The award also allowed KCU to expand the number of SSRF opportunities, giving more KCU students the chance to take part in research.

“This is exactly what an NIH R15 is meant to do — give our students the chance to roll up their sleeves and work on research that matters,” Creamer said. “KCU is doing a great job growing its research footprint — bringing in more grants, building infrastructure and opening more doors for students to get involved. The group of student doctors we had in the lab this summer was outstanding — engaged, curious and highly collaborative. Experiences like this can shape how they approach patient care for the rest of their careers. The work we’re doing could help patients, improve outcomes and give these future physicians and dentists a deeper understanding of how science drives medicine.”

Two of the Fellows, Whitney Dye and Adam Youssef, concentrated on breast cancer. Dye, a dental student with an interest in oncology, tested supplements commonly used by breast cancer patients, such as black licorice root, kratom and medicinal mushrooms, to see if they activated PXR. Her interest reflects the growing field of dental oncology, where dentists work alongside cancer teams to help patients manage the oral side effects of chemotherapy and radiation. While often marketed for benefits ranging from pain relief to immune support, these supplements can also carry risks. She discovered that several supplements clearly triggered PXR activity, a finding that could influence how cancer drugs are metabolized and how they interact with other medications. “It’s one thing to learn pathways from a PowerPoint,” Dye said. “It’s another to see them in action and understand how they might affect real patients.”

Youssef, an aspiring surgeon, worked with a triple-negative breast cancer cell line, an especially difficult type to treat because it’s missing the key features that many cancer drugs are designed to target. His project aimed to determine whether overexpressing PXR could reduce inflammation, which is often linked to cancer progression. While his results are still being analyzed, Youssef said the experience changed how he approaches scientific questions and collaborative problem-solving. “This was my first real wet lab experience,” he said. “It taught me how to collaborate, troubleshoot and think critically — skills that directly translate to working in a surgical team.”

Russell Bodily, Vi Nguyen and Cameron Ballard formed a colon cancer research team. For Bodily, a first-year dental student, the project began before he officially started classes. After relocating to Missouri early in the year, he connected with current students and faculty, interviewed with Staudinger and Creamer and joined the NIH-funded initiative months ahead of his first semester. His research took an unexpected turn when he discovered that the colon cancer cell line he was using didn’t express certain inflammation-related genes as expected. The finding forced him to pivot, focusing instead on drug and lipid metabolism pathways to better understand the cells’ behavior. “It’s bridged the gap between my undergraduate research and dental school,” Bodily said. “I’ve learned how to sift through literature and know what’s credible.”

Nguyen investigated cordyceps, a parasitic fungus used in traditional medicine, to see if it altered protein levels involved in drug metabolism, lipid metabolism and cell cycle regulation. She was surprised to uncover a possible link between cordyceps and ketogenesis – the way the body produces ketone bodies for energy – a connection rarely documented in scientific literature. “Seeing firsthand the work it takes to prove a pathway made me appreciate even more the science behind how we treat patients,” Nguyen said.

Ballard studied lion’s mane mushroom, often taken for cognitive benefits, to determine its effects on inflammation, metabolism and cell cycle pathways in colon cancer cells. While his results showed minimal changes, the data still contributed to the team’s broader understanding. The experience also reinforced the value of negative results in scientific progress. “Even when results aren’t what you hoped, they still contribute to the bigger picture,” Ballard said. “Working in the lab has made what we learn in the classroom more tangible and meaningful.”

Beyond technical skills, the students say the experience changed the way they think about patient care. Youssef learned that gene variability means standard treatments may not suit every patient, opening the door to personalized medicine. Bodily and others honed their ability to critically evaluate research – key to making sound clinical decisions – while Dye and Nguyen now view treatments and supplements through a whole-body lens.

For these future physicians and dentists, their time working together served as a reminder that the best care starts long before a patient walks through the door. It begins with curiosity, collaboration and a deeper understanding of the science behind every decision.

Research reported in this story was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15CA287338. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

_20240830165031_0.png?w=140&h=140)

(0) Comments